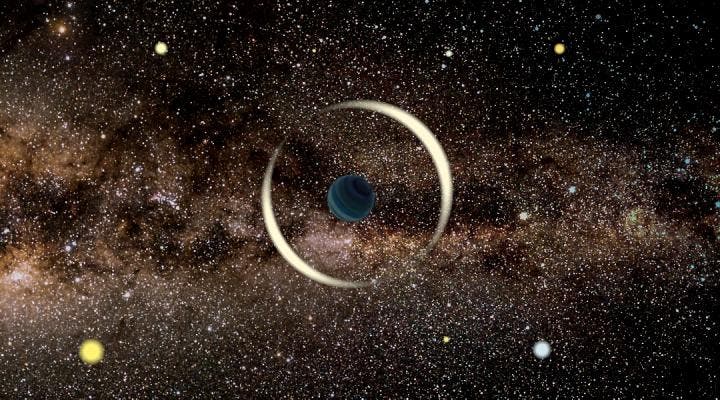

Astronomers have, for the first time, provided direct evidence confirming that a solitary, starless planet is wandering through the Milky Way. While a dozen “rogue planets” have been documented over the past ten years, this instance is not merely an informed supposition based on hints. By examining the same brief cosmic alignment from both Earth and space, researchers directly calculated the celestial object’s mass. They determined that this orphan is in the same mass range as Saturn, indicating that the galaxy is populated with abandoned exoplanets — formed within solar systems but later cast into the void, as stated by Subo Dong, an astronomy professor at Peking University in Beijing.

The discovery, detailed in the journal Science, implies that some “rogue planets” develop like typical planets before their violent rejection. “For the first time, we possess a direct measurement of a rogue planet candidate’s mass, rather than just a rough statistical inference,” remarked Dong, who directed the research. “We can confirm it is indeed a planet.”

Researchers established the planet’s mass by observing a transient event from both Earth and space, overcoming a long-standing challenge in studying wandering planets. These rogues are difficult to identify as they emit minimal light and do not orbit any stars. Astronomers have discovered them solely through gravitational microlensing, which happens when an object comes in front of a distant star, temporarily amplifying the star’s light due to gravitational effects. The observable flicker may last from hours to days, after which it vanishes.

Scientists calculated the distance and mass of the rogue planet employing the principles of parallax, which provides humans with depth perception. “In the absence of a host star, standard detection methods, such as the transit technique — detecting an exoplanet by observing slight dimming of a star’s light as it transits in front of it — cannot be applied,” explained Gavin A. L. Coleman, a researcher from Queen Mary University of London. “At present, the only method available for discovering rogue planets is gravitational microlensing.”

Until now, microlensing observations have not been able to definitively ascertain the distances to these planets, complicating the independent calculation of their masses. This uncertainty left scientists relying on conjectural estimates, calling into question whether the sources were truly planets or small, failed stars known as brown dwarfs. Some experts even speculated whether the objects could be something entirely unknown.

The recent finding stems from a microlensing event in May 2024. Ground-based observatories detected a brief, two-day brightening of a star located toward the bulging center of the galaxy. By coincidence, the European Space Agency’s Gaia star-survey satellite — positioned about 1 million miles from Earth — also recorded the event.

The two observational perspectives enabled the calculation of microlens parallax, analogous to human depth perception. Humans can perceive depth as a scene appears slightly different from each of their eyes, determined by the distance between them. “We utilize the same principle to derive the distance information of this rogue planet candidate, obtaining the mass and distance individually,” Dong stated. “The difference is that the distance between human eyes spans a few centimeters.”

The timing of the observed event was approximately two hours apart between the ground-based telescopes and Gaia. This delay provided insights into the object’s distance, and when combined with other data, its mass was ascertained. The object weighs around 22 percent of Jupiter’s mass and is situated roughly 9,800 light-years away. No host star was detected in the data, further suggesting that the planet is either free-floating or in an extremely vast orbit, making its distant star undetectable.

The planet’s relatively low mass is significant because objects that are several times Jupiter’s mass — brown dwarfs — can originate in isolation, akin to small stars. However, an object like Saturn is far more likely to have formed in a planet-forming disk surrounding a star, and later ejected. This expulsion likely occurred through cosmic collisions, close encounters with other celestial bodies, or the unpredictable gravitational pull of an unstable star.

The study bolsters the notion that planet ejection is a prevalent component of planet formation. Upcoming missions, including NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, are anticipated to significantly expand the catalog of known rogue planets and elucidate how often worlds are displaced. If they are plentiful, it’s possible that developing solar systems routinely lose one or two planets during the process.

“So far,” Dong remarked, “we only have a glimpse into this emerging population of rogue worlds and the insights they may provide regarding the formation of celestial bodies in the universe’s planetary systems.”