Scientists might have made a mistake years ago by designating Uranus and Neptune as the “ice giant” planets in the solar system. Similar to labeling a short-armed dinosaur as “terrible lizard king,” referring to these planets as “icy” has not stood the test of time. Recent research from the University of Zurich indicates that this label may have been incorrect, suggesting that the two blue planets could be more rock-like than icy.

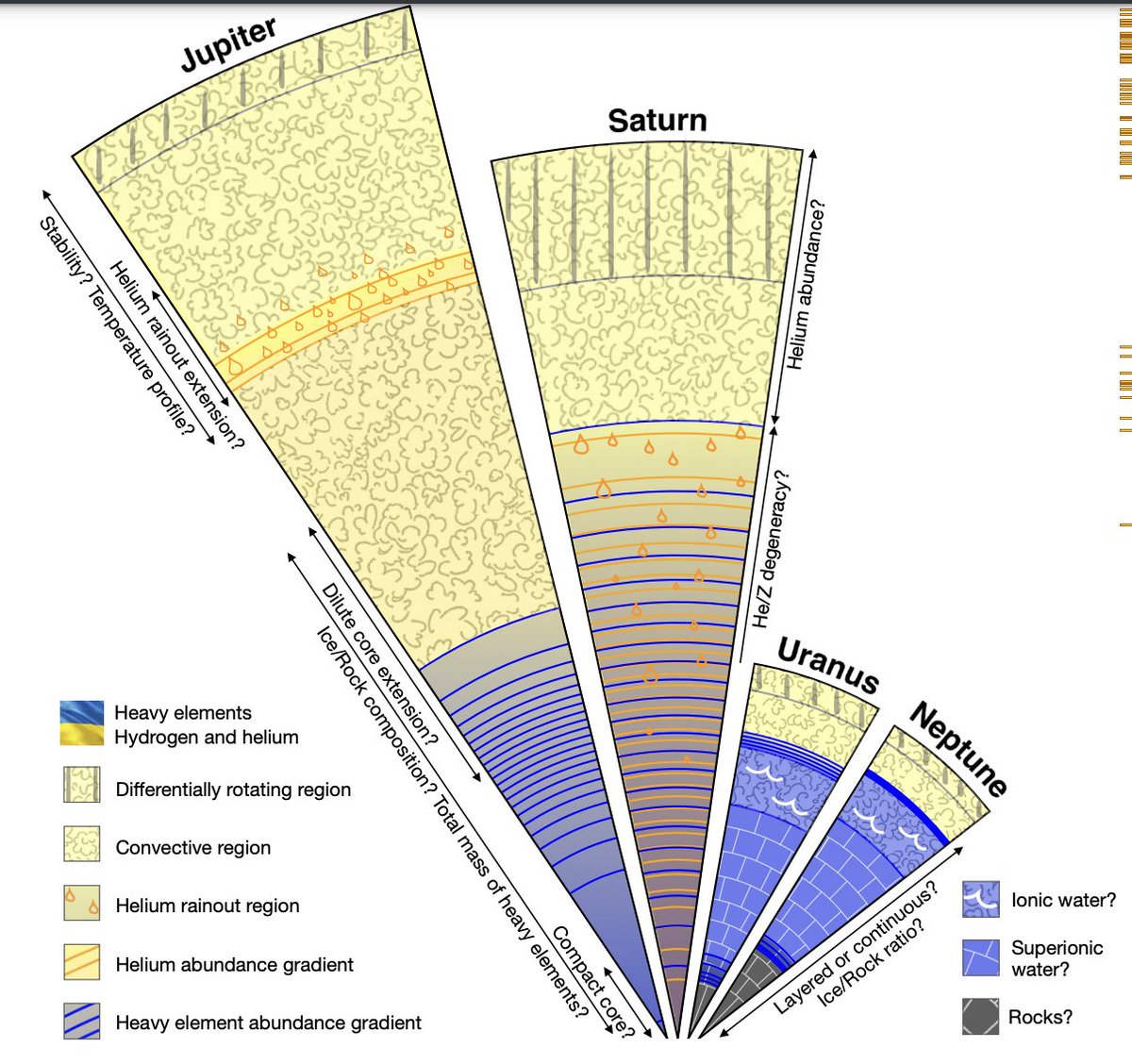

These distant, frigid planets were originally termed “ice giants” to set apart their compositions from Jupiter and Saturn, the “gas giants” abundant in hydrogen and helium. Uranus and Neptune are smaller in size compared to their gaseous relatives but larger than Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

However, there is limited knowledge regarding these mid-sized outer planets, which represent the least-studied category within our solar system. NASA’s Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft that has approached them, performing flybys of Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

“This term is somewhat misleading since it suggests that the planets are primarily composed of water,” stated Ravit Helled, an astrophysicist who led the research. “The term ‘ice giants’ also conveys the notion that the planets are solid, but materials in their deep interiors may exist in a liquid form.”

The findings carry significance for the exploration of exoplanets—worlds orbiting stars besides the sun—and indicate that further observations and theories are necessary before determining internal composition. The group’s challenge to the “ice giants” designation is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

To achieve their conclusions, the researchers formulated a new model to investigate what exists deep within Uranus and Neptune without adhering to rigid assumptions. They started with random estimations of the density for each layer, then utilized a computational method to refine these estimates until they correlated with actual measurements of each planet’s gravity, adhering to established principles regarding material behavior under pressure and heat.

Their findings reveal that both planets might have significantly different internal compositions. Some models indicate a water-dominated structure, while others are abundant in rock. There is no definitive answer regarding the predominant material of these planets.

If the planets were more rocky, it might suggest they originated closer to the sun and later migrated outward. Some scientists have theorized this, Helled noted.

“Numerous studies on dynamics propose that Uranus and Neptune formed nearer to the sun,” she remarked.

All viable composition models incorporate moving, swirling layers of electrically charged water, termed “ionized water.” These layers could potentially account for the unusual, asymmetrical magnetic fields observed around both planets. The internal temperatures might remain sufficiently high for hydrogen, helium, and water to remain mixed rather than segregating.

The outer layers also vary. Uranus appears to contain a greater amount of hydrogen and helium near its surface compared to Neptune. The area responsible for generating Uranus’ magnetic field is likely situated deeper within the planet than that of Neptune.

However, understanding their true characteristics will necessitate dedicated missions to the planets. A spacecraft could analyze their gravitational fields and atmospheric compositions. For the time being, it is reasonable to assert that the internal structures of medium-size planets are more intricate than previously believed, and it might be appropriate to consider retiring the “ice giant” label.

“We could continue to use this term,” Helled noted, “as long as people realize that it does not automatically represent the planetary composition and material conditions.”