Researchers have located a significant, well-structured spiral galaxy that emerged shortly after the Big Bang, when the universe was approximately 1.5 billion years old. Dubbed Alaknanda, this galaxy was detected using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope during extensive sky surveys. Its light has journeyed over 12 billion years to reach Earth, demonstrating the remarkable abilities of contemporary telescopes to discern such distant galaxies in detail.

For many years, astronomers were convinced that galaxies in the early universe were too tumultuous to develop orderly spiral shapes, with young stars and gas moving in an irregular fashion. Observations from the Hubble Space Telescope reinforced this idea, as spiral galaxies seemed uncommon beyond 11 billion years in look-back time. This finding puts previous beliefs about early galaxy formation into question.

“Alaknanda shows that the early universe was capable of assembling galaxies much quicker than we previously believed,” stated Yogesh Wadadekar, a co-author of the study. “This galaxy managed to accumulate 10 billion solar masses of stars into a spiral disk in merely a few hundred million years, prompting astronomers to reevaluate galaxy formation theories.”

Webb’s enhanced resolution has revealed numerous disk-shaped galaxies from the early universe, including an increasing number of genuine spiral galaxies like Alaknanda, earlier than older theories had forecasted. In 2023 and 2024, the telescope uncovered two spiral galaxies, CEERS-2112 and REBELS-25, from the early universe.

The discovery of Alaknanda, attributed to researchers at the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in India, was published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

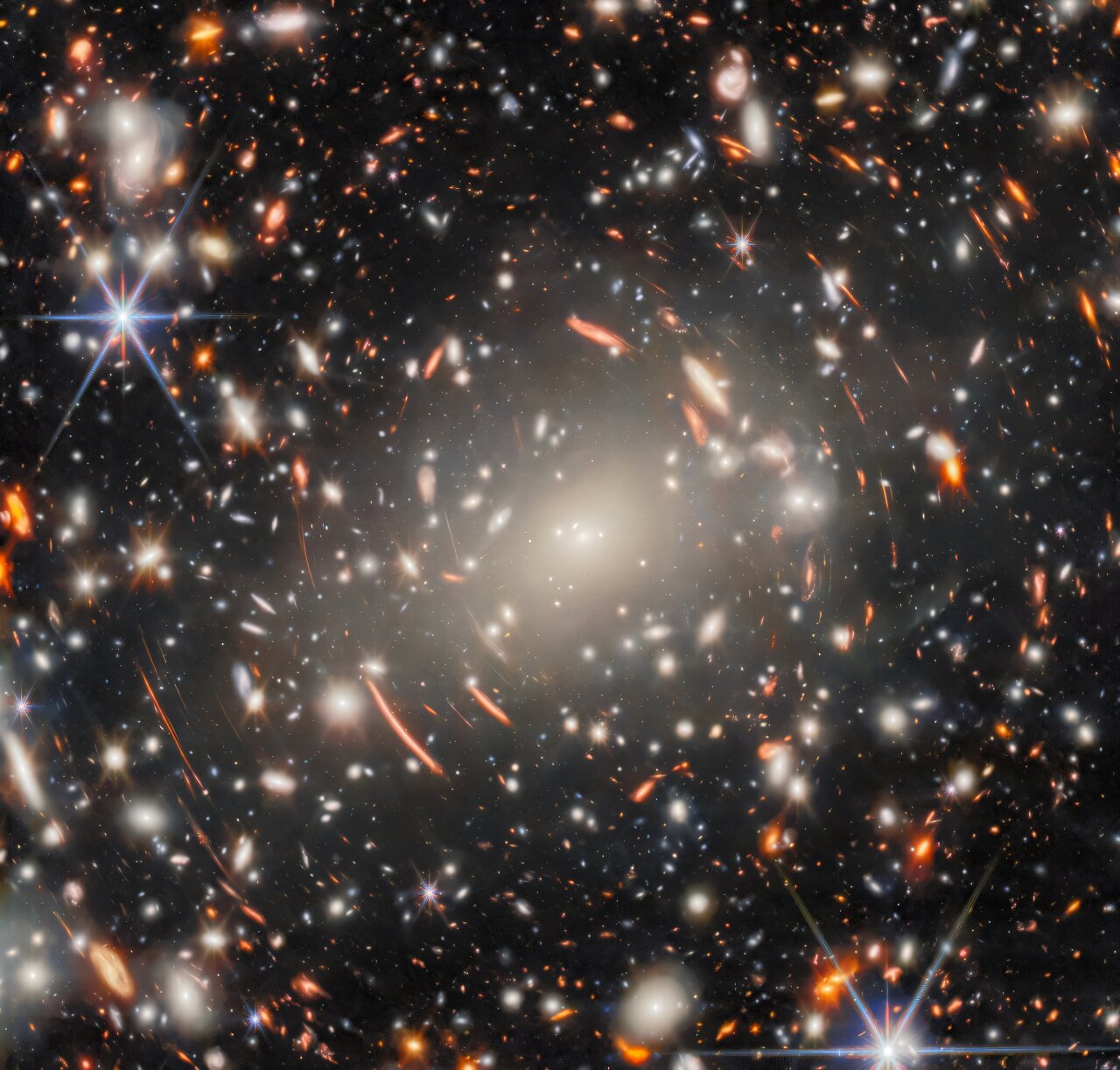

The research team examined Alaknanda in great detail using gravitational lensing, where the gravity of a massive galaxy cluster acts as a magnifying glass, amplifying the light from Alaknanda. “The mechanisms driving galaxy formation can function more effectively than current models suggest,” said Rashi Jain, the lead author. “This is compelling us to rethink our theoretical framework.”

Alaknanda, named after a river in the Himalayas, extends roughly 32,000 light-years, comparable to substantial modern spiral galaxies, and contains a massive number of stars. Images portray a flat, rotating disk with two distinct spiral arms in a classic pinwheel arrangement, earning it the designation of a “grand-design” spiral galaxy.

Along the spiral arms, scientists detected strings of bright clusters of newborn stars, resembling a sequence of beads where gas has collapsed into dense regions igniting new stars. Each string seems to be part of a larger spiral arm.

By analyzing Alaknanda’s brightness across 21 different wavelengths of light, researchers estimated that the galaxy’s stars are on average about 200 million years old, indicating a swift surge of star formation after the universe exceeded 1 billion years in age. Alaknanda continues to expand rapidly, creating new stars at a rate of approximately 63 suns per year, significantly faster than the Milky Way today.

The genesis of spiral arms in these ancient systems is still not well understood. Some theories propose that they result from slow-moving density patterns within disks, while others attribute them to gravitational disruptions from nearby galaxies or large gas clusters. Alaknanda may have a minor neighboring galaxy that could have impacted its spiral structure, but further evidence is required.

Upcoming observations utilizing Webb’s instruments and radio telescopes could chart how Alaknanda’s stars and gas revolve around its center, aiding in determining whether its disk has stabilized into a final form or if the spiral arms are merely a transient phase.